Our ability to assess the ecological effects of microplastics across all levels of biological organization with this level of realism is unprecedented.

Research Questions

Some hypotheses are not easy to test in laboratory experiments. Moreover, complex interactions generally cannot be observed. That’s why we are using whole-ecosystem science to better understand how microplastics are impacting freshwater lakes. In collaboration with the IISD-Experimental Lakes Area, we are able to manipulate an experimental lake (Lake 378) by adding microplastics in a way that mimics stormwater runoff, a major source of microplastics to waterways.

Our research intends to answer questions surrounding the fate and of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems, as well as the effects for biota to help inform policy around risk management and mitigation:

- Understanding the physical, chemical, and biological fate of microplastics in lakes and their watersheds;

- How microplastics impact aquatic ecosystems across all levels of biological organization;

- How ecosystem processes and functions (e.g. nutrient cycling, photosynthesis, primary productivity) are affected by microplastics; and

- The recovery of an exposed ecosystem, including microplastic degradation and transformation.

Experimental Design

We are using a Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) design to evaluate the impacts of microplastics on an experimental lake (Lake 378) compared to a control lake (Lake 373). Lake 378 is being loaded with an environmentally relevant amount of microplastics, while Lake 373 remains unmanipulated. The microplastics used in this study are a mixture of polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyethylene terephthalate – some of the most common types of microplastic polymers found in the environment. Each polymer is a different colour (yellow, pink, blue) to help facilitate tracing, and varies in buoyancy (positively buoyant, neutrally buoyant, negatively buoyant). Both lakes are measured for baseline conditions prior to the addition of microplastics, and will continue to be monitored for years following manipulation. Being able to look at data from before and after human intervention (i.e. the addition of microplastics) is an extremely useful tool to help us understand the true impact microplastics are having on freshwater ecosystems which can help to inform policy decisions surrounding risk management and monitoring.

Background & Baseline Sampling

Background Microplastic Sampling

In 2019 we measured background microplastic concentrations in lakes at IISD-ELA. This was done to establish the background levels of microplastic contamination in bottom sediments, surface water, and atmospheric deposition in a remote boreal ecosystem. Microplastics were found in all matrices and across all the lakes that were sampled. Moreover, we learned that microplastic contamination in these remote lakes is most likely from atmospheric transport, not from local point sources.

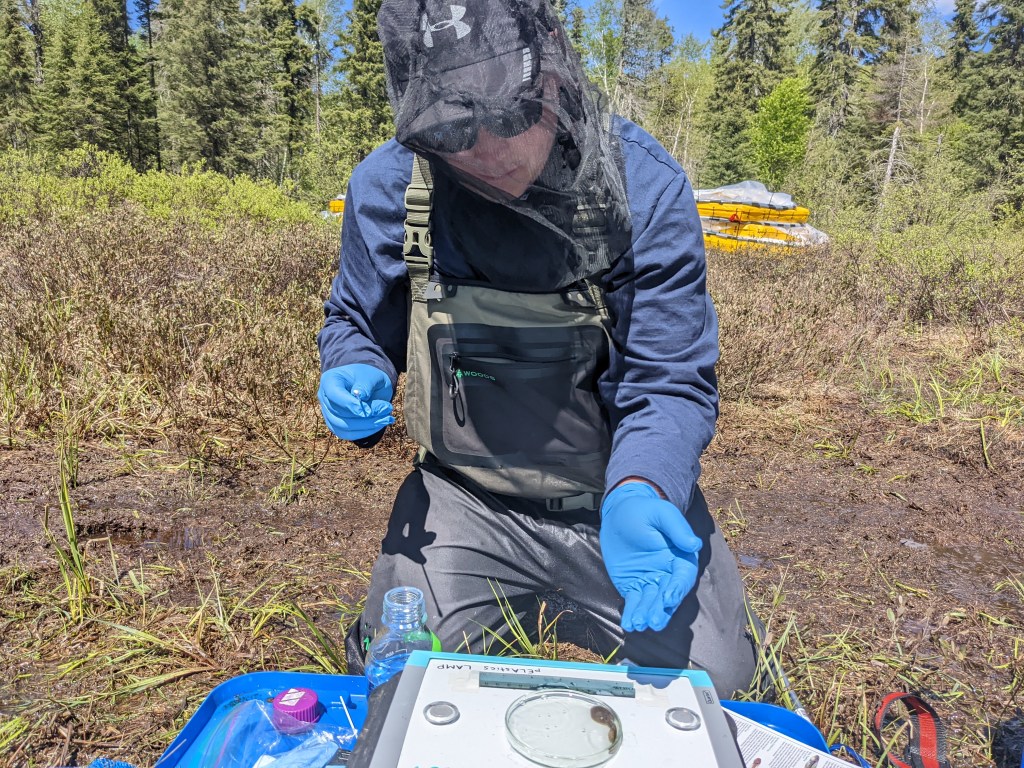

Ecological Baseline Sampling

Starting in 2019 we began collecting baseline ecological data for our experimental lake (Lake 378) and a reference lake (Lake 373) so that we could compare the before and after conditions once microplastics were added to Lake 378. We assessed the baseline conditions of the water (nutrients, chemistry, water clarity), and the populations and communities of organisms living in the lakes, including phytoplankton, zooplankton, benthic and emerging invertebrates, amphibians and fish.

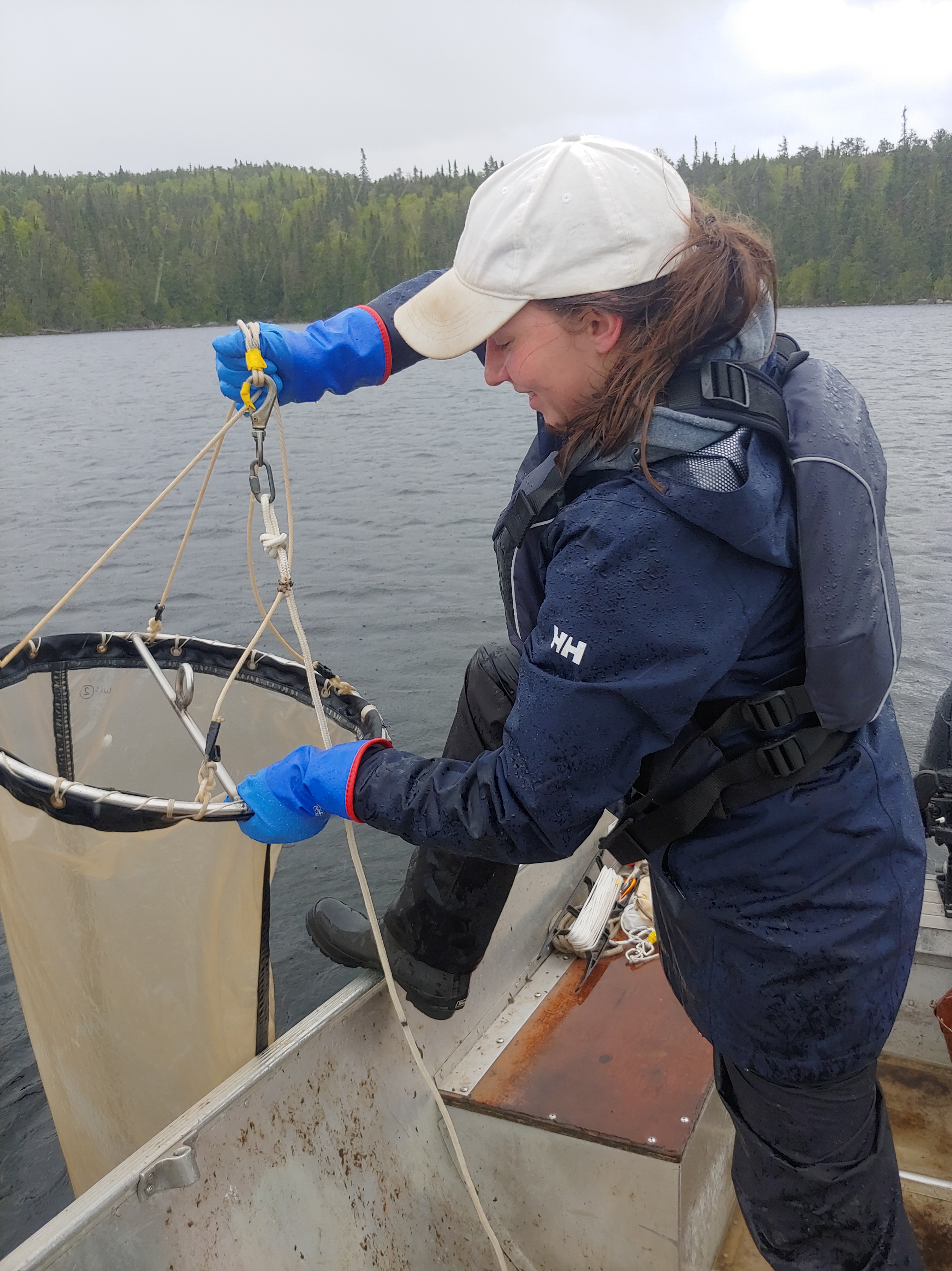

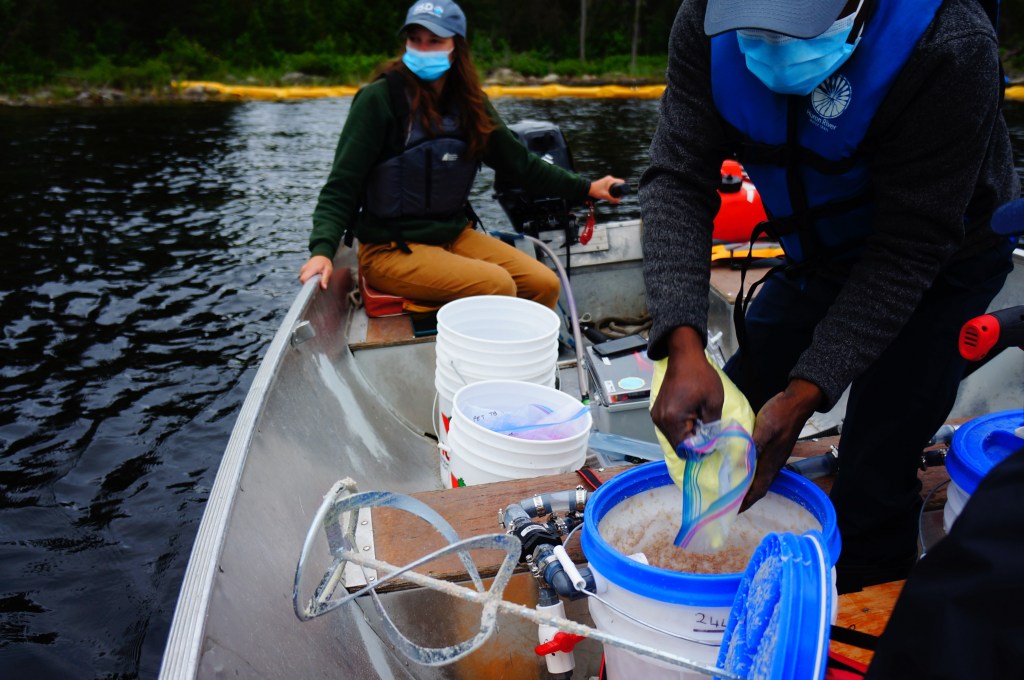

Microplastic Additions

Microplastic additions to Lake 378 began in in summer 2023. Microplastics are added biweekly during the ice-free season to simulate stormwater runoff. Three types of common microplastics (polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyethylene terephthalate) are added as an even mixture by mixing them vigorously with lake water and dispensing them underwater behind a boat. For this we use a microplastic addition system that was developed by David Tuck, a student at the Ingenuity Labs at Queen’s University. The microplastics are released along the perimeter of the lake and along transects (each 25 m apart) that run horizontally across the lake. The transects are followed using mapping software (Topo Maps Canada). Our goal is to distribute the microplastics as evenly as possible across the lake so that any horizontal distribution of microplastics is not due to the way in which we added the microplastics.

Sampling for Fate and Effects

During the 3 years of microplastic additions, we will continue to monitor the water chemistry and the individuals, populations, and communities of organisms living in the lakes to measure any changes caused by microplastics. This includes water chemistry and quality, phytoplankton, zooplankton, benthic and emerging invertebrates, amphibians and fish. Understanding how microplastics impact freshwater ecosystems can help inform policies relevant to risk management.

We will also be monitoring where the microplastics end up in the lake (e.g., the sediment, shoreline, and water column) and in the aquatic food web (e.g., zooplankton, invertebrates, and fish). Understanding where microplastics end up in a freshwater ecosystem can help inform policies relevant to monitoring, exposure, and mitigation.

Mitigation & Long Term Monitoring

After the 3 years of microplastic additions are finished in 2025, we will continue to monitor Lake 378 for ecosystem recovery. This will include sampling and measuring the fate of microplastics over time and across matrices, including measuring burial within the sediment. Non-invasive cleanup methods will also be tested to help learn best practices for removing microplastics from contaminated lakes. This phase will inform policies relevant to mitigation.